This Howto explains how to set up a Linux server that runs SSH, WireGuard VPN, Forgejo (a fork of Gitea, a web-based git forge, kinda like self-hosted Github) behind a local nginx reverse proxy and a minimal DNS server so we can have an internal domain for pretty URLs. It also shows how to set up a minimal MTA/mail forwarder so the server can send mails, an iptables + SSHGuard-based firewall, automated backups and some basic self-monitoring. As a bonus there’s a short section that outlines how to set up OpenProject in this environment.

To follow this Howto you’ll need (very) basic Linux commandline knowledge, i.e. you should be

able to navigate the file system in a terminal, use SSH and edit textfiles with a terminal-based

text editor (like nano, joe or vim, whatever you prefer).

It will assume that you’re using Ubuntu Server 22.04, but it should be the same for other

(systemd-using) Debian-based Linux distributions, and reasonably similar when using other distributions.

You’ll also need full root privileges on the system.

Hopefully this Howto is also useful if you only want to do some of these things (maybe set up a public Forgejo instance, or just a Wireguard server without Forgejo on it).

UPDATE: There was a bug in the backup and monitoring scripts (shouldn’t have used

bash_function | tee foolog.txt), so I updated them accordingly.

UPDATE 2: Added something about configuring

[git] HOME_PATH in Forgejo’s app.ini, which works

around a Forgejo bug that prevents blobless clones.

UPDATE 3: Some small changes, and added a section about denying Git users SSH access unless they’re coming through the Wireguard VPN.

UPDATE 4: Replaced suggestion for using Hetzner with a warning about them.

Note: You’ll often need to enter commands in the shell. The following convention will be used:

$ some_command --some argument

means: Enter “some_command --some argument” (without quotes) in a Linux terminal, as normal user.

# some_command --some argument

means: Enter “some_command --some argument” (without quotes) in a Linux terminal, as root,

or maybe with sudo (you can use $ sudo -i to get a root-shell so you don’t have to use sudo

for each command).

Motivation

You can skip this section if you’re already convinced that this Howto is relevant for you ;-)

We needed a git server with a web frontend.

It should be low-maintenance, because we’re a small company that doesn’t have a dedicated admin who

could regularly spend time on keeping the server up-to-date, especially when running external

software packages where updates might require more steps than a sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade.

To be honest, we would probably just pay a service like Github or Gitlab or whatever, if they had

offers that meet our requirements at a reasonable price - but we create games (and related products),

which means we don’t only have code, but also lots of binary data (game assets like models and textures),

even relatively small projects can easily have checkout sizes (without history!) of dozens of GB,

bigger projects often use several hundreds of GB or more. Nowadays Git supports that reasonably well with

Git Large File Storage (LFS)1, and while several Git hosters generally support LFS,

prices for data are a bit high: Gitlab’s takes $60/month for packs of 10GB of storage and 20GB

of traffic.. Githubs prices are a bit less ridiculous with “data packs” that cost $5/month

for 50GB of data and 50GB of traffic, but if you have a 40GB repo you’ll already need a second

data pack if you do more than one full clone per month.. this doesn’t scale that well.

So self-hosting is a lot more attractive, as you can get a VPS (Virtual Private Server,

basically a VM running “in the cloud”) with several hundreds of GB storage for < €20/month,

and S3-style “object storage” (that can be used for Git LFS data) for about €10 per 1TB per month2.

To host Git (and get a nice Github-ish frontend) we use Forgejo, a fork of Gitea. It’s written in Go and is just a single executable with few external dependencies (it needs a database, but supports sqlite, which should be good enough for up to at least 10 users3). It can store the LFS data directly in the filesystem on the servers disk, but also supports storing it in S3-compatible (external) object storage.

We work decentralized, most people at home, so the server needs to be accessible over the

internet.

However, to keep maintenance low (while maintaining reasonable security), we “hide” Forgejo

behind a Wireguard VPN, so:

- The only network ports open to the internet are those of Wireguard and SSH, which both are installed from the standard distro packages (and thus can be easily updated) and are known to have good security (arguably I could also hide SSH behind Wireguard, but I’d like to be able to get on the server with SSH directly even if Wireguard should fail for some reason. I’ll make SSH public-key-auth-only, so I don’t have to worry about bruteforcing attacks on the user passwords).

- This means that we don’t have to worry that Forgejo might have a vulnerability that allows unauthenticated users to run code (Gitlab had such an issue a few years back), because only our team can access it at all, so if we forget to update Forgejo for a while, we’ll still be safe4.

- We can use plain HTTP (instead of HTTPS), because all connections to Forgejo go through the encrypted Wireguard tunnel, so we don’t have to mess around with SSL certificates.

And of course, if we need other web-based services (like maybe a fancier bugtracker) those can be run and protected in the same way.

Configuring SSH for public key authentication

If you rent a (virtual private) server with Linux, you’ll most probably get SSH access, likely with

a password.

It’s more secure (and possibly more comfortable) to use SSH public key authentication (which is also

what’s usually used with Git). For this a cryptographic key-pair, consisting of a private and a public key,

is generated on clients (like the computer you’re using) that should be able to connect to the server

with SSH

Here you’ve got two options: Using your default SSH key, or creating one specifically for this server.

1. Use your default SSH key

Check if you already have a default SSH public key, it’s in $HOME/.ssh/id_rsa.pub (on Windows

C:\Users\YourUserName\.ssh\id_rsa.pub, on Linux something like /home/yourusername/.ssh/id_rsa.pub).

If not, you can create it by running

$ ssh-keygen

in a terminal. Confirm that you want to save

it in the default place (which should be the one mentioned above) and enter a password that will

be used to locally decrypt the key, for extra security.

When connecting to a SSH service that has public key authentication enabled, it will be used by default.

You might be asked for the password of your SSH key then, which is the one you set in ssh-keygen.

2. Creating one for this server

You can create an SSH key pair just for this server, possibly with a different password than the one you’re using for your default SSH key.

To do this, just run:

$ ssh-keygen -f /path/to/keyfile

This will create /path/to/keyfile (private key) and /path/to/keyfile.pub (public key).

You’ll have to tell the SSH client to use this keyfile with ssh -i /path/to/keyfile example-host.com

… or you create an entry in $HOME/.ssh/config for the host:

# my VPS for hosting git

Host example-host.com

# or whatever user you're using for logging in

User root

HostName example-host.com

IdentityFile /path/to/keyfile

then $ ssh example-host.com will automatically set the username and the keyfile

Enabling your public SSH key on the server

Of course you need to tell the server your SSH public key so it can use it to authenticate your

connections. To do this, on the server edit the file $HOME/.ssh/authorized_keys (create it if

it doesn’t exist) and add a line with the contents of the public key file from your local machine

($HOME/.ssh/id_rsa.pub or /path/to/keyfile.pub).

Verify that this works by logging out of the server and logging in again (if you’re using an SSH

key specific to this server, remember to pass the -i /path/to/key option to SSH).

It should ask for a password for the key file, like Enter password for key '/path/to/keyfile':,

not for the host (that prompt would look like username@host password:). Enter the password you

chose when creating the key file and you should be on the server.

If this didn’t work as expected, you’ll have to debug and fix that problem.

Once it works go on with the next step:

Disable SSH login with password

Now that you can log into the server with public key authentication, logging in with a password can be disabled, to prevent attackers from bruteforcing the password.

NOTE: If your server hoster supports creating snapshots of the server, now would be a good time to take one, so you can just restore it in case anything goes wrong here and you can’t log in anymore (shouldn’t happen if this is done correctly and you verified that logging in with public key authentication works, but better safe than sorry).

As root (or with sudo) edit /etc/ssh/sshd_config and search for a line that contains

“PasswordAuthentication” and change it to PasswordAuthentication no - make sure to remove any #

characters from the start of the line as they comment it out!

If there is no line with “PasswordAuthentication” yet, just add the PasswordAuthentication no line

somewhere in the middle of the config, before any lines that start with “Match”, like “Match user asfd”.

Do the same to ensure that a ChallengeResponseAuthentication no line exists.

NOTE: While editing the servers

sshd_config, you could also make another change that will make Git fetches faster by allowing Git to use the Git (wire) protocol version 2.

Search for a line that starts withAcceptEnvand addGIT_PROTOCOLat the end.

If no such line exists, just add a lineAcceptEnv GIT_PROTOCOL.

Save the file and restart the SSH server to make sure the changed config is loaded:

# systemctl restart sshd

If that failed for some reason, systemctl status sshd should show some information on the cause.

Setting up a WireGuard VPN server

Install WireGuard

# apt install wireguard-tools

If the Linux kernel you’re using is older than 5.6 (check with $ uname -r), also install wireguard-dkms

to get the WireGuard kernel module (it’s included in Linux 5.6 and newer).

Basic setup of the server

NOTE: This is a quite basic configuration of WireGuard, suitable for this particular usecase. It fully supports IPv6 (but here having IPv4 addresses in the VPN is sufficient) and can be configured in other ways than the classic “one VPN server with several clients” scenario used here.

If you’ve already got a wireguard connectionwg0configured, just give it another name likewg1, so whenever this Howto mentionswg0, usewg1instead.

Wireguard requires a private and corresponding public key for the server (and also

for each client, we’ll get to that later).

Create a directory that only root can access to store them in:

# mkdir /root/wireguard && chmod 700 /root/wireguard

# cd /root/wireguard && umask 077

Now use WireGuards wg tool with the genkey command to generate a new private key

(stored it in a file called wg_privatekey.txt):

# wg genkey > wg_privatekey.txt

and the pubkey command to generate the public key (wg_publickey.txt) from the private key:

# cat wg_privatekey.txt | wg pubkey > wg_publickey.txt

The easiest way to set up a WireGuard network device (here it’s called wg0) is creating a config

for the wg-quick tool.

As root create a textfile at /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf with the following content:

# configuration of this server (its IP in the VPN, what port to listen on etc)

[Interface]

# the private IP the server will have in the VPN and its subnet (e.g. /24)

Address = 172.30.0.1/24

# the UDP port wireguard will listen on - 51820 is WireGuards default port

ListenPort = 51820

# the servers private key

# replace "YourPrivateKey" with the private key stored in wg_privatekey.txt

PrivateKey = YourPrivateKey

NOTE: In WireGuard configurations (and lots of other kinds of config files and scripts), lines starting with

#are comments. They’re ignored by WireGuard and are meant to provide information to humans reading those files. In this case that’s you, or other people who might want to modify your WireGuard configs later.

Make sure it’s only readable by root (it contains your private key, after all!):

# chmod 600 /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf

Address should be a

private IPv4 address

that doesn’t conflict with your LAN/WIFI at home, in the office or wherever this is going to be used.

/24 at the end of the IP is the subnet mask of the network we’re creating (equivalent to

255.255.255.0), meaning we can have up to 254 different IPs in the VPN (in this case 172.30.0.1

to 172.30.0.254; the first and last IPs - 172.30.0.0 and 172.30.0.255 in this example - have special

meanings); see Wikipedia (Subnetwork) for details.

Of course you could choose a different IP and subnetwork, including one that’s bigger (like a /20),

whatever suits your needs.

This is enough to get the wireguard network interface up:

# wg-quick up wg0

creates a WireGuard interface wg0 based on the settings in /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf.

You can verify that it worked with:

# ip address show wg0

the output should look like:

3: wg0: <POINTOPOINT,NOARP,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1420 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/none

inet 172.30.0.1/24 scope global wg0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

That’s a good start, but so far no one will be able to connect to this server, as no clients have been configured yet.

Configure a new client, on the client

This must be done on the client machine that’s supposed to connect to the server!

This is similar to the server configuration. First you’ll need to install wireguard, of course, see the WireGuard Installation page for installers for several operating systems including Windows.

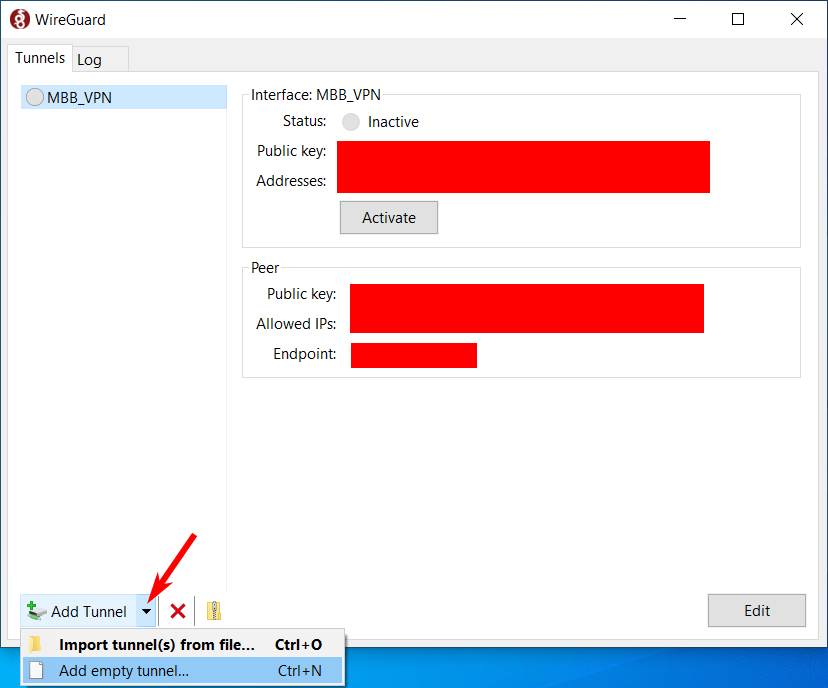

… on Windows

Start the WireGuard application, or right-click the wireguard icon next to the clock of your taskbar and select “Manage tunnels…”

Then add an empty VPN tunnel:

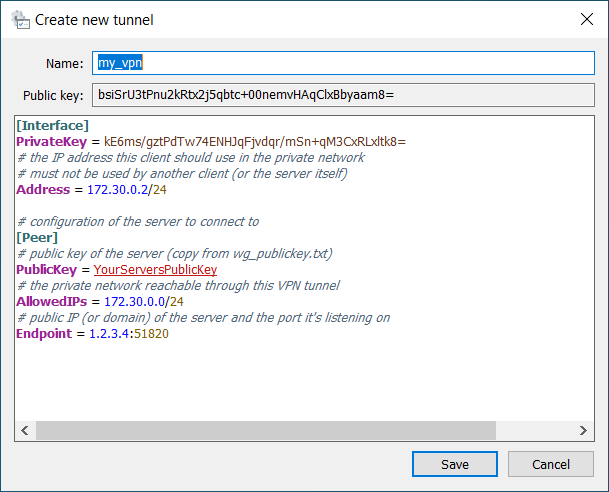

And configure it:

A new PrivateKey is automatically generated and set (and the PublicKey is set from it),

but you’ll have to add the other settings shown on the screenshot (of course adjusted to your needs).

For Name, just pick a sensible name. Or a nonsensical one, I don’t care :-p

See the Linux section below for more explanation of the other settings.

Note that you’ll need the Public Key later, so you can already copy it somewhere.

Click Save. You can’t activate the connection yet though, this new client must first be added

to the server configuration, see below.

… on Linux and similar (using wg-quick)

Like on the server, create a /root/wireguard/ directory, make sure only root can access it and

create a private and a public WireGuard key:

# mkdir /root/wireguard && chmod 700 /root/wireguard

# cd /root/wireguard && umask 077

# wg genkey > wg_privatekey.txt

# cat wg_privatekey.txt | wg pubkey > wg_publickey.txt

Create /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf on the client with the following contents:

# settings for this interface

[Interface]

# this client's private key

PrivateKey = ThisClientsPrivateKey

# the IP address this client will use in the private network

# must not be used by another client (or the server itself)

Address = 172.30.0.3/24

# configure a DNS server for a custom local domain

# only relevant on Linux, will be set in a later chapter

#PostUp = TODO

# the server we're gonna connect to

[Peer]

# public key of the *server*

PublicKey = YourServersPublicKey

# AllowedIPs is used for routing (only) that network through the tunnel

AllowedIPs = 172.30.0.0/24

# public IP or domain of the server and the port it's listening on

Endpoint = yourserver.example.net:51820

- The

[Interface]section configures the WireGuard network interface of this client. It has the following settings:- PrivateKey is the private key of this client. On Windows this line is generated

automatically, on Linux use the private key you just generated (in

/root/wireguard/wg_privatekey.txton the client). - Address must be an unused address in the private network you configured as “Address”

on the server.

Note that it must have the same subnetmask,

/24in my example. - PostUp lets you set a command that’s executed when the connection is established.

Not available on Windows (unless explicitly allowing it in the registry).

Commented out for now because it only makes sense after the DNS chapter below.

- PrivateKey is the private key of this client. On Windows this line is generated

automatically, on Linux use the private key you just generated (in

- The

[Peer]section configures the server this client will connect to:- PublicKey is the public key of the server, if you followed the instructions

above it’s saved in

/root/wireguard/wg_publickey.txton the server, so replace “YourServersPublicKey” with the contents of that file. - AllowedIPs is the private network reachable through this tunnel, note that it uses

172.30.0.0as IP (the first IP of the subnet), which has the special meaning of representing that subnet. Used by WireGuard to ensure that only IPs in that network are routed through the tunnel. - EndPoint configures the public address and port of the WireGuard server that the client connects to. Replace “yourserver.example.net” (or “1.2.3.4”) with the correct IP or domain.

- PublicKey is the public key of the server, if you followed the instructions

above it’s saved in

Now the VPN connection is configured on the client, but won’t work just yet, because the server must be told about the new client first.

NOTE: As the administrator of the WireGuard server, it make sense to have a copy of a client configuration in a local text file, without the PrivateKey, as a template for future clients - the only things that must be adjusted per client are the PrivateKey and the Address (I also replace the last part of the Address IP with

TODOto make sure I don’t forget to set a new IP when copy&pasting it to a new client configuration).

… on macOS

No idea, I don’t have a Mac :-p

There seems to be a WireGuard App in the App Store and looking at this tutorial I found it seems to be pretty similar to the Windows one, so you should be able to get it to work :-)

Add new clients to the server configuration

On the server, open /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf in a text editor (as root).

At the end of the file, add the following (this example adds two clients, if you only created one,

add only one [Peer] section):

### List of clients that can connect to the VPN ###

# Heinrichs Windows PC

[Peer]

# replace with the real public key of the client

# (copied from the clients tunnel configuration)

PublicKey = bsiSrU3tPnu2j5qbtc+00nemvHAqClxBbyaam8=

# the IP the client gets, must be the same as in the "Address"

# in the clients config !! but with /32 at the end !!

AllowedIPs = 172.30.0.2/32

# make sure the connection stays alive, esp. if NAT routers are involved

PersistentKeepalive = 21

# Daniels Linux Laptop

[Peer]

# replace "DanielsPublicKey" with the public key of the client

# (from the clients wg_publickey.txt)

PublicKey = DanielsPublicKey

# the IP the client gets, must be the same as in the "Address"

# in the clients config !! but with /32 at the end !!

AllowedIPs = 172.30.0.3/32

# make sure the connection stays alive, esp. if NAT routers are involved

PersistentKeepalive = 21

# TODO: add more clients in the future, make sure they all use different IPs

# and that everyone has their own [Peer] section

Note that, unlike on the client, AllowedIPs must have /32 as subnet mask

(meaning all bits are masked, i.e. it only refers to this one IP), because only

traffic for that IP should be routed to that particular client5.

Now you can tell WireGuard to reload the config:

# wg syncconf wg0 <(wg-quick strip wg0)

.. and now the clients should be able to connect (on Windows by clicking Activate for the tunnel,

on Linux with # wg-quick up wg0).

Note that clients can only communicate with the server, not with each other, and they don’t access the internet through that tunnel, at least without setting up ip forwarding on the server (see footnote6).

PersistentKeepalive = 21 makes sure that a (possibly empty) network packet is sent at least every

21 seconds to make sure that routers and firewalls between the client and the server don’t assume

the WireGuard connection is closed when there’s no real traffic, see also

this more elaborate explanation.

NOTE: If you’re wondering why the client and the server need to know each others public keys, that’s for security. When a WireGuard client connects to a WireGuard server, the server uses its copies of the clients public keys to identify the client (make sure the client is allowed to connect at all, and set client-specific options like their IP). The client on the other hand uses its copy of the servers public key to make sure that the WireGuard server it’s connecting to really is the one it wants and not just an attacker who somehow redirected traffic meant for your WireGuard server to a server controlled by the attacker. For the general concept, see also Wikipedia on Public-key cryptography

Configure the server to automatically start the connection

While you should have a working WireGuard VPN tunnel now, it won’t work anymore if the server is rebooted. So let’s tell the server to automatically start the wireguard server. Luckily the wireguard-tools Ubuntu package provides a systemd service that works with WireGuard devices configured with a wg-quick config, so we don’t have to do much.

To be sure there’s no conflicts, first take the interface down:

# wg-quick down wg0

Then enable the systemd service and start it:

# systemctl enable wg-quick@wg0.service

# systemctl start wg-quick@wg0.service

Check its state with:

# systemctl status wg-quick@wg0.service

If you modify wg0.conf, instead of calling # wg syncconf wg0 <(wg-quick strip wg0) as shown above,

you can now also run:

# systemctl reload wg-quick@wg0.service

NOTE: You could do the same on Linux clients of course, if you want to start the

wg0connection to the server automatically at boot.

It might be a good idea to reboot the server and to make sure everything still works as expected after the boot.

A simple firewall with iptables and SSHGuard

Before setting up any more services, let’s create some simple firewall rules that block all

connection attempts from the internet, except for ones to SSH and WireGuard.

Furthermore SSHGuard is used to block hosts that are attacking our

SSH server.

Install SSHGuard and ipset:

# apt install sshguard ipset

Configure sshguard by editing /etc/sshguard/sshguard.conf (as root) and replace the

BACKEND=... line near the top of the file with

BACKEND="/usr/libexec/sshguard/sshg-fw-ipset"

so SSHGuard stores the IPs that should be blocked in an ipset that

can be used in iptables rules. Save the file, then restart SSHGuard so it applies the changed config:

# systemctl restart sshguard.service

NOTE: If your server hoster supports creating snapshots of the server, now would be a good time to take one, so you can just restore it in case something goes wrong with the firewall rules we’re about to create and you lock yourself out

By default, Ubuntu ships the UFW firewall.

This Howto uses plain ip(6)tables, so disable ufw7:

# systemctl stop ufw.service

# systemctl disable ufw.service

I suggest putting the firewall scripts into /root/scripts/, so create that directory.

Create one script called firewall-flush.sh in that directory that removes all firewall rules

and allows all connections:

Download firewall-flush.sh

Click to show the script

#!/bin/sh

# This script resets ip(6)tables so all connections are allowed again

echo "Flushing firewall (iptables) rules"

# flush (remove) all existing rules

iptables -F

iptables -t nat -F

iptables -t filter -F

iptables -t mangle -F

# set INPUT policy to ACCEPT again

# (otherwise it'd remain at DROP and no connection would be possible)

iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT

echo ".. same for IPv6 (ip6tables) .."

# flush all existing rules

ip6tables -F

ip6tables -t nat -F

ip6tables -t filter -F

ip6tables -t mangle -F

# reset ip6tables INPUT policy to ACCEPT

ip6tables -P INPUT ACCEPT

Then create a second script firewall.sh with the actual firewall rules

(see the comments in the scripts for a little explanation of what it does).

Note that you might have to modify the WAN network device name. It’s the network device

connected to the internet - it might be called eth0, but names like enp5s0 or similar

are also common. Just adjust the WAN="eth0" line accordingly8.

firewall.sh: Download firewall.sh

Click to show the script

#!/bin/sh

# Daniels little firewall script

# Makes sure that we only accept SSH and wireguard connections

# from the internet. All other services (like http for the git tool etc)

# are only allowed via wireguard VPN (dev wg0)

# the network device connected to the internet

WAN="eth0"

# the VPN device (for connections to services not publicly exposed)

VPN="wg0"

echo "Creating IPv4 (iptables) firewall rules.."

# flush all existing rules

iptables -F

iptables -t nat -F

iptables -t filter -F

iptables -t mangle -F

# by default (as policy) allow all output, but block all input

# (further down we add exceptions that allow some kinds of connections)

iptables -P INPUT DROP

iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# Now some rules for incoming connections are added, each with iptables -A,

# so they'll be evaluated in this exact order

# allow all connections on the loopback device lo (localhost, 127.x.x.x)

iptables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

# if for some broken reason we get packets for the localhost net that are

# are *not* from lo, drop them

# (if they're from lo, the previous rule already accepted them)

iptables -A INPUT -d 127.0.0.0/8 -j DROP

# for now, allow all incoming connections from VPN (wireguard) peers

# (*could* be limited to the ones actually needed: UDP 53 for dnsmasq,

# TCP 22 for ssh/git, TCP 80 for http)

iptables -A INPUT -i $VPN -j ACCEPT

# SSHGuard detects SSH bruteforce attacks and adds their source IPs

# to the sshguard4 (or sshguard6 for IPv6) ipsets.

# So block connections from IPs in the set:

iptables -A INPUT -i $WAN -m set --match-set sshguard4 src -j DROP

# generally allow traffic for established connections

# (this includes replies to outgoing connections )

iptables -A INPUT -m state --state ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

# accept SSH connections on port 22 (unless sshguard has dropped them first)

iptables -A INPUT -i $WAN -p tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPT

# also accept connections to the wireguard server

iptables -A INPUT -i $WAN -p udp --dport 51820 -j ACCEPT

# some useful ICMP messages that we should probably allow:

iptables -A INPUT -p icmp --icmp-type fragmentation-needed -j ACCEPT

iptables -A INPUT -p icmp --icmp-type echo-request -j ACCEPT # ping

echo ".. now doing (basically) the same for IPv6 (ip6tables)"

# flush all existing rules

ip6tables -F

ip6tables -t nat -F

ip6tables -t filter -F

ip6tables -t mangle -F

# by default (as policy) allow all output, but block all input

# (further down we add exceptions that allow some kinds of connections)

ip6tables -P INPUT DROP

ip6tables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# allow all connections on localhost (::1)

ip6tables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

# .. but no connections that have a localhost address but are not on lo

ip6tables -A INPUT -d ::1/128 -j DROP

# Note: not creating any ip6tables rules for wireguard-internal traffic

# (on wg0), as we only use IPv4 for that private internal network

# drop all packets from IPv6 addresses that sshguard detected as attackers

ip6tables -A INPUT -i $WAN -m set --match-set sshguard6 src -j DROP

# generally allow traffic for established connections

# (this includes replies to outgoing connections )

ip6tables -A INPUT -m state --state RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

# accept SSH connections on port 22 (unless sshguard has dropped them first)

ip6tables -A INPUT -i $WAN -p tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPT

# also accept connections to the wireguard server

ip6tables -A INPUT -i $WAN -p udp --dport 51820 -j ACCEPT

# allow the ICMPv6 types required for IPv6

# (and ping, it's always useful if you can ping your server)

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 1 -j ACCEPT # dest unreachable

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 2 -j ACCEPT # packet too big

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 3 -j ACCEPT # time exceeded

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 4 -j ACCEPT # parameter problem

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 128 -j ACCEPT # echo request (ping)

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 133 -j ACCEPT # router solicitation

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 134 -j ACCEPT # router advertisement

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 135 -j ACCEPT # neighbor solicitation

ip6tables -A INPUT -p ipv6-icmp -m icmp6 --icmpv6-type 136 -j ACCEPT # neighbor advertisement

Make both scripts executable:

# chmod 755 /root/scripts/firewall*

The safest way to test the firewall script is like this (executed in /root/scripts/):

# ./firewall.sh ; sleep 60 ; ./firewall-flush.sh

It will apply the firewall rules, then wait for 60 seconds, and then remove them again.

So you have one minute to test the rules, and if something went wrong and the rules lock

you out, you only have to wait for a minute and you can connect to the server again.

You could test if you can:

- ping the server - on your local machine run:

$ ping yourserver.example.com

(replace “yourserver.example.com” with your servers domain or IP) - create new SSH connections:

$ ssh -S none user@yourserver.example.com

(replace “user” with the username you’re using to normally log in to that server)

-S nonemakes sure that a new connection is established by disabling SSH connection sharing. - connect with WireGuard - if a connection is currently active disable it, then enable it again

(on Linux with

# wg-quick down wg0and# wg-quick up wg0), then try to ping your server through wireguard ($ ping 172.30.0.1)

(make sure the rules are still active and haven’t been flushed yet; you could of course sleep for

longer than a minute, e.g. sleep 300 for five minutes)

You show display the current iptables rules for IPv4 by entering:

# iptables-save

and for IPv6:

# ip6tables-save

(you could also use iptables -L -v or ip6tables -L -v if you find that output more readable)

If this all works, create a systemd service to ensure that the firewall script is automatically run on boot.

Create a file /etc/systemd/system/firewall.service with the following contents:

## Systemd service file for Daniels little firewall script

## makes sure that the firewall (iptables) rules are set on boot

[Unit]

Description=Firewall

Requires=network.target

After=network.target

[Service]

User=root

Type=oneshot

RemainAfterExit=yes

ExecStart=/root/scripts/firewall.sh

ExecStop=/root/scripts/firewall-flush.sh

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Enable and start the firewall service:

# systemctl enable firewall.service

# systemctl start firewall.service

Check with # iptables-save if the iptables rules have been created, reboot, make sure you still get

on the server (and the iptables rules are still/again there).

By the way: If it takes a while after boot until WireGuard is started, the systemd network-online.target

might be hanging (the wg-quick service waits for that). You can check this by executing

# systemctl status systemd-networkd-wait-online.service

If the output says something about a timeout (instead of “Finished Wait for Network to be Configured.”),

execute

# networkctl

If the state of a device is “configuring” instead of “configured” or “unmanaged”, that explains

why systemd-networkd-wait-online.service didn’t succeed (and then gave up after a timeout so

services that wait for it at least start eventually).

At least on our server the problem was that for some reason systemd’s networkd doesn’t properly

finish configuring a device if IPv6 is disabled, as it is the default on a Contabo VPS.

Contabo provides a command that can be executed to enable IPv6 (but this is Contabo-specific, if

other hosters also disable IPv6 by default and you run into the same problem, refer to their documentation!):

# enable_ipv6

NOTE: If your hoster offers VNC access to your server (which gives you access to a terminal even if you can’t reach the server through SSH anymore) and enables it by default (like Contabo does), now that your firewall is working without locking you out is a good time to disable the VNC access, so no one can try to break into your server through that.

Setting up dnsmasq as DNS server for a local domain

This step will set up dnsmasq for the local

example.lan domain, so Forgejo will be reachable (in the VPN) under http://git.example.lan.

This isn’t strictly needed, at least if you only host one http service on the server (or use different

ports for different services) - then you could access them with http://172.30.0.1 or

http://172.30.0.1:3000 - but it’s definitely nice to have.

Of course you can use a different domain, like yourcompany.lan, but I think that using the nonexistant .lan top-level-domain is a good idea for this purpose9. Alternatively you could use a subdomain of a real domain you have, like vpn.yourcompany.com (and then maybe git.vpn.yourcompany.com), but to be honest I’m not completely sure how that would be set up properly10.

We’ll install and configure it to only listen on wg0 and to answer queries for *.example.lan.

Install the dnsmasq package:

# apt install dnsmasq

Stop its systemd service, as its standard configuration clashes with systemd-resolved (and is not

what we need anyway):

# systemctl stop dnsmasq.service

NOTE: If you’re already using dnsmasq on your server, or want to use it for something else as well, you can create alternative instance configurations as described in the systemd howto included in the dnsmasq debian/Ubuntu package (which relies on the dnsmasq systemd service as defined in that package) to run multiple instances of dnsmasq at once. For the sake of simplicity, this Howto assumes that’s not needed and uses the standard config.

As root, edit /etc/default/dnsmasq

- Add the line

DOMAIN_SUFFIX="example.lan"(or “yourcompany.lan” or whatever you want to use); make sure it’s the only not commented-out line that sets DOMAIN_SUFFIX - Uncomment the

IGNORE_RESOLVCONF=yesline (so it’s in there without a#before it) - Uncomment (or add) the

DNSMASQ_EXCEPT="lo"line to ensure that dnsmasq will not be used as the systems default resolver.

Save the file and now edit /etc/dnsmasq.conf - in its initial states, all lines should be commented

out (begin with #).

The following lines should end up in dnsmasq.conf:

# don't use resolv.conf to get upstream DNS servers

# in our case, don't use any upstream DNS servers,

# only handle example.lan and fail for everything else

# (VPN clients shouldn't resolve their normal/global domains here)

noresolv

# answer requests to *.example.lan from /etc/hosts

local=/example.lan/

# only listen on the wireguard interface

interface=wg0

# only provide DNS, no DHCP

no-dhcp-interface=wg0

# This option (only available on Linux AFAIK) will make sure that:

# 1. like with bind-interfaces, dnsmasq only binds to wg0 (instead of

# binding to the wildcard address on all devices and then only

# replying to requests on the requested device)

# 2. this works even with interfaces that might dynamically appear

# and disappear, like VPN devices

bind-dynamic

# this (and the next option) expands simple hosts like "horst"

# from /etc/hosts to "horst.example.lan"

expand-hosts

domain=example.lan

(You could also delete or rename /etc/dnsmasq.confand create a fresh one that only contains

the lines shown above)

Next edit /etc/hosts. dnsmasq uses hosts configured in that file to answer DNS requests.

Add the lines

172.30.0.1 www.example.lan example.lan

172.30.0.1 git.example.lan

(if you want to use other aliases for other services add them as well, for example

172.30.0.1 openproject.example.lan)

Now start dnsmasq again:

# systemctl start dnsmasq.service

Configure clients to use the DNS server

The VPN clients must be told to use the DNS server you just set up.

Linux and other Unix-likes

On Linux distros that use systemd-resolved (are there other Unix-likes that use systemd?),

replace the #PostUp = TODO line line in the client’s /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf with:

PostUp = resolvectl dns %i 172.30.0.1; resolvectl domain %i ~example.lan; resolvectl default-route %i false

(yes, that must all go in one line to work!).

resolvectl dns %i 172.30.0.1sets 172.30.0.1 as the network-interface-specific DNS server (Note that%iwill be replaced with the interface name bywg-quick)resolvectl domain %i ~example.lansetsexample.lanas the default domain for that interface, and the~prefix makes it a “routing (-only) domain”, which means that all requests to that domain (and its subdomains), in this case*.example.lan, should go to the DNS server(s) configured for this interface.resolvectl default-route %i falsemeans that this interfaces DNS server should not be used as the default DNS server for DNS requests for domains not explicitly configured as “routing domains”. This ensures that the dnsmasq running on172.30.0.1will only be used to resolveexample.lan,git.example.lan,www.example.lanetc, not any other domains likeblog.gibson.shorraspi.myhome.lanorxkcd.com.- See man resolvectl, man systemd.network and this article for more information.

For this setting to take effect, you’ll have to disconnect and reconnect the wireguard connection

on the client (# wg-quick down wg0 && wg-quick up wg0)

On other distributions or operating systems (that don’t use systemd-resolved),

this might be a bit harder, and depend on what they’re using exactly, anyway.

Some of them use the resolvconf package/tool to manage /etc/resolv.conf, but as far as I know

and according to this serverfault.com answer, it only supports setting global DNS servers

(that are used for all domains), and a suggested workaround is to install dnsmasq or similar on the

client and configure dnsmasq to use 172.30.0.1 for example.lan (and another DNS server for

all other requests) - the required line in dnsmasq.conf on the client would be

server=/example.lan/172.30.0.1.

A simple workaround if you don’t want to set up your own local caching DNS server (like dnsmasq):

Edit /etc/hosts on the client and add the hosts you need, like

172.30.0.1 git.example.lan www.example.lan whateverelse.example.lan

Of course it means that if another subdomain is added on the server, you also need to add it locally,

but depending on your usecase this might be the path of least resistance…

NOTE: wg-quick allows setting a

DNS = 1.2.3.4option under[Interface].

Even with a default search domain, likeDNS = 172.30.0.1, example.lan.

DO NOT USE THAT!

It sets the global DNS server, meaning, it will be used for all your DNS requests, not just the ones forexample.lan- that’s most probably not what you want, and when dnsmasq is configured like described here it won’t even work (as it won’t know how to resolve other domains likegibson.shorgoogle.com)!

Furthermore, it only works with resolvconf, not systemd-resolved or Windows (AFAIK).

Windows

On Windows, WireGuard doesn’t support PostUp scripts (unless explicitly enabled in the registry), because apparently there are bigger security implications than on Linux.

So instead of setting the DNS server when connecting and removing it when disconnecting, just

configure it once and leave it configured, by entering the following command in an

Administrator PowerShell:

Add-DnsClientNrptRule -Namespace 'example.lan','.example.lan' -NameServers '172.30.0.1'

As this explicitly sets the DNS server only for *.example.lan, it shouldn’t hurt much

that the server isn’t reachable when the WireGuard connection is down - it just means that the DNS

request will timeout and fail in that case.

NOTE: If you want to remove the rule again, entering

Get-DnsClientNrptRulein an (Administrator) PowerShell will list rules including their “Name” identifiers, and

Remove-DnsClientNrptRule -Name "{6E6B2697-2922-49CF-B080-6884A4E396DE}"deletes the rule with that identifier.

macOS

Again, I can’t test this myself because I don’t have a Mac, but I found a blog post that looks relevant.

The gist of it (in case it disappears in the future):

Create a textfile /etc/resolver/example.lan that contains the line

nameserver 172.30.0.1

Apparently this doesn’t work for all tools though (not for dig, for example), but according to

the blog post,

$ scutils --dns can be used to check if the setting was applied, and ping should also work.

The blog posts suggests trying a reboot in case it doesn’t work at all.

I hope that it works with git, git-lfs and your web browser - if you try it,

please let me know how it went in a comment! :-)

Testing the DNS server

Now on the client you should be able to ping the new domains (if the WireGuard connection is active):

$ ping example.lan

$ ping git.example.lan

Setting up nginx as a reverse http proxy

nginx will be used as a webserver/reverse proxy, that makes

http://www.example.lan and http://git.example.lan and possibly other domains available,

redirecting them to other services based on the subdomain used (for example, the real git server, Forgejo,

will listen at port 3000/tcp, instead of the standard http port 80/tcp, and OpenProject, that nginx could provide at http://openproject.example.lan, listens on port 6000/tcp).

Install it with:

# apt install nginx-light

(at least for the purposes documented in this tutorial, you won’t need the additional features

provided by the full nginx package)

The Debian/Ubuntu configuration of nginx (maybe other distros do the same) splits up the site-specific

nginx-configuration into one little config per site; they’re configured in /etc/nginx/sites-available/*.conf,

to actually enable a site, its config is symlinked to /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/.

By default, only /etc/nginx/sites-available/default exists (and is enabled), it shows the

static page from /var/www/html/index.nginx-debian.html (or index.htm or index.html in the same directory).

I’d suggest keeping it like this; you could edit that default index.html to provide links to the pages

with content, like http://git.example.lan (once they exist..).

You should however make one little change to /etc/nginx/sites-available/default:

Replace the listen 80 default_server; line with listen 172.30.0.1:80 default_server; to make

sure that nginx only listens on the WireGuard IP and not on all IPs.

As we’ll soon install Forgejo, we can already configure the site for it in nginx by creating

/etc/nginx/sites-available/git with the following content:

server {

# should be reachable on port 80, only on WireGuard IP

listen 172.30.0.1:80;

# the domain that's used (=> will be available at http://git.example.lan)

server_name git.example.lan;

# nginx defaults to a 1MB size limit for uploads, which

# *definitely* isn't enough for Git LFS.

# 'client_max_body_size 300m;' would set a limit of 300MB

# setting it to 0 means "no limit"

client_max_body_size 0;

location / {

# Forgejo will listen on port 3000, on localhost

proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:3000;

# http proxy header settings that are required

# according to the Forgejo/Gitea documentation:

proxy_set_header Host $host;

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-Proto $scheme;

}

}

Then create a symlink in /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/:

# ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/git /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/git

and restart the nginx service:

# systemctl restart nginx.service

Now you can already test it and it should work, but it likely won’t work after rebooting,

because nginx will likely start before the WireGuard device (that provides the IP nginx is supposed

to listen on) is ready, and because of that will fail.

To fix this we’ll have to tell the nginx systemd service to start after WireGuard (wg-quick@wg0).

That’s done with:

# systemctl edit nginx.service

which will open a text editor (with lots of stuff that’s commented out) that allows you to

specify additional rules that overwrite the ones in the system nginx.service

(at /usr/lib/systemd/system/nginx.service; the override rules are saved in

/etc/systemd/system/nginx.service.d/override.conf). All that’s needed here are the following lines:

# tell systemd to start this service (nginx) after wg0 is up

# (=> wg-quick@wg0 service is done)

# so nginx can bind to the WireGuard device's IP

[Unit]

After=wg-quick@wg0.service

(ok, the first three lines are just comments and not really needed).

Save and exit the editor (if it’s GNU nano, press Ctrl-X, then type y for “yes I want to save”

and press enter to confirm the preselected filename).

With this change, if you reboot, nginx should (still) work.

If you need to, you can edit this again with the same command (# systemctl edit nginx.service).

Now if you open a browser on a desktop PC connected to the server with WireGuard (that

has the DNS server configured as described in the previous chapter), you should be able to open

http://example.lan and http://git.example.lan (though the latter will show an error page because

Forgejo isn’t installed yet).

Note that you might have to actually type the whole URL including http:// in the browser,

because nowadays browsers only open URLs without protocol (http://) for known top level domains,

otherwise they’ll open a web search using “git.example.lan” or whatever you typed in as search

query11..

As mentioned before, this uses plain HTTP, no HTTPS encryption, because:

- That would be a PITA to set up for a custom/local domain (you’d have to create your own pseudo-CA and import that at every client)

- The connection to the server is already encrypted with WireGuard, so it already is secure (even if your webbrowser may claim otherwise because it doesn’t know that detail)

- Not only is additional HTTPS encryption unnecessary, it’d also be additional overhead, both on the server and client CPUs that have to encrypt/decrypt the traffic twice and on the network bandwidth, as both WireGuard and SSL/TLS (used by HTTPS) add their own metadata to each packet, in addition to the http message you actually want to send/receive.

NOTE: If you want to host Forgejo publicly, much of this article still applies (you’d just leave out the wireguard and DNS server parts). In that case you absolutely should use HTTPS of course, and the place where you’d configure it would be the nginx configuration. See the nginx HTTPS documentation and their blog post on using Let’s Encrypt (if you want to use free Let’s Encrypt SSL certificates) and this Howto on installing Gitea with nginx and Let’s Encrypt SSL.

Setting up dma as sendmail implementation

It’s useful for a server to be able to send E-Mails.

That can be used to tell you that an error happened, that updates are available, or it can just

be notifications from Forgejo or other software about new (comments on) bug reports, merge requests etc.

The standard way to do this on Unix-like systems is the /usr/sbin/sendmail tool; originally part of a fully fledged mailserver, but nowadays several different programs implement that functionality, including minimal ones that don’t implement SMTP themselves but just send a mail through a configured external SMTP server.

This shows how to set up such a simple sendmail replacement, specifically dma, as running a full mailserver isn’t exactly straightforward and also is against the idea of exposing as few possibly vulnerable services on this server to the internet as possible.

So the idea is that you already have some E-Mail account that provides SMTP access (a freemailer, your company mailserver, whatever), ideally with a special noreply-address just for this server.

Of course the first step is to install dma:

# apt install dma

On Debian and Ubuntu, during the installation, you’ll be asked to configure dma.

The “System Mail Name” shouldn’t matter much, you can leave it at its default, the “Smarthost”

is the SMTP server you want to use.

Afterwards, you’ll most probably still have to do some manual changes to the configuration, so (as root)

edit /etc/dma/dma.conf and:

- set

PORT 465(for TLS/SSL encrypted communication with the SMTP server) - uncomment the

#AUTHPATH /etc/dma/auth.confline (remove the#at the beginning of the line) so auth.conf with the smtp server login data will be used (we’ll edit that next) - uncomment

#SECURETRANSFERso TLS/SSL is used - set

MASQUERADE noreply@yourdomain.com(with the noreply address you want to use for this) to make sure that when sending mails it always uses that address as sender; your mailserver might even reject mails that set other senders

Now edit /etc/dma/auth.conf to set the login data for the smtp server by adding a line like:

noreply@yourdomain.com|smtp.yourdomain.com:YourPassw0rd

where smtp.yourdomain.com is the same domain you set as “Smarthost”.

For other users than root to be able to use dma (or sendmail) to send a mail, the configs must

be readable by the mail group. Check with:

$ ls -lh /etc/dma/

If the lines don’t look like -rw-r----- 1 root mail 250 May 15 15:28 auth.conf, but show

another group than mail (maybe root root), change the ownership to user root, group mail, with:

# chown root:mail /etc/dma/*.conf

For further information see the dma manpage and the ArchWiki’s dma page.

NOTE: In case the E-Mail account you want to use is from GMail (or

Google AppsG SuiteGoogle Workspace), setting this up is a bit more painful, as by default Google doesn’t support standard SMTP login anymore, but only OAuth2 based login (which is not supported by dma or other similar tools that I know of). It requires setting up an “App Password”, see the Google documentation for that or this tutorial from Mailreach (though note that Google UI has changed slightly since it was created, to get to the screen to create an App Password you currently need to click, in your normal mail view, the user button on the upper right -> Manage your Google Account -> Security -> How you sign in to Google -> 2-Step Verification and select “App Passwords” there).

Also potentially useful: This article on turning a Google-hosted E-Mail address into a No-Reply address that rejects mails sent to it. (Note that it might take 15 minutes or so until that rejection rule is in effect)

Also note that this is no endorsement for GMail (in fact I suggest not to use it), but if you (or your company or project) are using it anyway, this information might be useful.

Testing the sendmail command

Sending a mail on the commandline or a from script with sendmail is easy: It the receiver addresses are commandline arguments and the mail subject and text is read from stdin.

So create a textfile like this:

Subject: This is a testmail!

This is the body of the test mail.

It's plain text.

You can probably somehow send HTML mails, but

1. I don't know how

2. Those suck anyway

Kind regards,

Your Server.

and then send the mail with:

$ /usr/sbin/sendmail name@example.com name2@example.com < mailtext.txt

The log files /var/log/mail.err and /var/log/mail.log help debugging mail issues.

Redirect local mails for root to your mail account

Some services like sending mails with information (esp. detected problems) to the local account of

the root user. When you log in via SSH, you might be told that there are new mails and you can

read them with the mail tool. As it is, that’s not overly useful, as you probably won’t regularly

log into your server once it’s set up.

Thankfully (due to dma supporting it), it’s super easy to redirect those mails to a real mail account:

Just create a file

/etc/aliases with the following line:

root: name@example.com

or, if multiple people should get those mails:

root: name@example.com, othername@example.com

This is even useful for mails from your own scripts (usually to indicate problems, see the backup

and the monitoring scripts below): You can just tell them to send mails to root, and then

configure who will actually get them (for example you and coworkers who administrate the server)

in this one central place, instead of hardcoding several E-Mail addresses all over the system.

You can test this as shown in the previous section, but with root as E-Mail address:

$ /usr/sbin/sendmail root < mailtext.txt

Setting up Forgejo for git hosting

NOTE: Forgejo is a fork of Gitea, and at least as of release 1.19.3 they’re very similar, so these instructions should work for both (if you replace “forgejo” with “gitea” in paths etc). Also, if you run into problems, searching your favorite search engine for

your problem "gitea"will probably give you more results thanyour problem "forgejo", so it’s worth trying. Similarly, if the Forgejo Documentation doesn’t answer your questions, check out the Gitea Documentation.

See The Forgejo FAQ for more information about the project and why they forked12.By the way, these Forgejo installation instructions roughly follow the Gitea Installation from Binary documentation (at time of writing, Forgejo didn’t have installation instructions yet13).

Install Forgejo and git, create git user

First, download the Forgejo binary for your CPU architecture and maybe verify the GPG signature, as described on the Forgejo download page.

Next, copy the downloaded Forgejo binary to /usr/local/bin/ (renaming it to just “forgejo”)

and make it executable:

# cp forgejo-1.19.3-0-linux-amd64 /usr/local/bin/forgejo

# chmod 755 /usr/local/bin/forgejo

Make sure git and git-lfs are installed:

# apt install git git-lfs

Create a user git on the system. Forgejo will run as that user, and when accessing git through ssh

(which is the default), this user is part of the URL (for example in

git clone git@git.example.lan:YourOrg/YourRepo.git the git before the @ is the user you’ll create now).

On Debian, Ubuntu and their derivates that’s done with:

# adduser --system --shell /bin/bash --gecos 'Git Version Control' \

--group --disabled-password --home /home/git git

On Linux distributions not based on Debian/Ubuntu (this should at least work with Red Hat derivates like Fedora, CentOS etc - feel free to leave a comment about other distros!), run this instead:

# groupadd --system git

# adduser --system --shell /bin/bash --comment 'Git Version Control' \

--gid git --home-dir /home/git --create-home git

If you haven’t already done it, you can configure the SSH daemon on your Git server to allow

setting the GIT_PROTOCOL environment variable, which allows Git clients to use Git protocol

version 2 which is more efficient.

See the NOTE in the Disable SSH login … section above.

Create directories Forgejo will use

Now create the directories Forgejo will use and set access rights appropriately:

# mkdir /var/lib/forgejo

# chown git:git /var/lib/forgejo && chmod 750 /var/lib/forgejo

This is the directory Forgejo will store its data in, including your git repos.

# mkdir /etc/forgejo

# chown root:git /etc/forgejo && chmod 770 /etc/forgejo

This is the directory Forgejos config, called app.ini, is stored in. It needs to be writable by

forgejo at least during the installation, and while Forgejo shouldn’t add files after the installation

is done and won’t modify the app.ini during normal operation, it might modify the app.ini on updates

(i.e. when first running a new version). So if, like suggested in some tutorials (and here as well,

in an earlier version of the article), you make the directory and app.ini read-only for the git user

after installation, keep in mind to make it writable again when doing an update - or just keep app.ini

writable.

Optional: Set up database

When using sqlite as Forgejos database, nothing needs to be done here.

If you need a more powerful database, you can use MySQL/MariaDB or PostgreSQL (apparently sqlite is good enough for at least 10 users, but might even suffice for more3. I heard that it’s possible to migrate the database from sqlite to something else later, though it isn’t guaranteed to work).

See Forgejos Database Preparation guide for setup instructions.

Install systemd service for Forgejo

Forgejo provides a

systemd service script.

Download it to the correct location:

# wget -O /etc/systemd/system/forgejo.service https://codeberg.org/forgejo/forgejo/raw/branch/forgejo/contrib/systemd/forgejo.service

If you’re not using sqlite, but MySQL or MariaDB or PostgreSQL, you’ll have to edit that file

(/etc/systemd/system/forgejo.service) and uncomment the corresponding Wants= and After= lines.

Otherwise it should work as it is.

NOTE: For Forgejo 1.19.x, make sure that

forgejo.servicesetsType=simple, notType=notifyand that theWatchdogSec=30sline either doesn’t exist or is commented out by prepending a#to it.

(The forgejo.service currently available in their main branch setsType=notify, and contains that Watchdog line, both only work with the current 1.20 development code, not release 1.19.3, see this bugreport).

Now enable and start the Forgejo service, so you can go on with the installation:

# systemctl enable forgejo.service

# systemctl start forgejo.service

Forgejos web-based configuration

You should now be able to access Forgejo in your local web browser, so open http://git.example.lan/ (make sure your WireGuard connection is enabled).

If it doesn’t work:

- Make sure the forgejo service started successfully by checking the output of

# systemctl status forgejo.service

If that indicates an error but the log lines underneath are too incomplete to tell what caused it,

# journalctl -n 100 --unit forgejo.service

will print the last 100 lines logged by Forgejo. - Try http://git.example.lan:3000/ instead - that’s the port Forgejo listens on, this way nginx is circumvented (later we’ll configure Forgejo to make it only accessible through nginx). If that works, fix your nginx setup.

- Try to ping

172.30.0.1- if that fails, make sure your WireGuard connection works - Try to ping

git.example.lan- if you can’t, fix your DNS setup (also on the client!)

You should be greeted by Forgejos “Initial Configuration” screen.

The settings should be mostly self-explanatory, some hints:

- Select the correct database (SQLite3, or if you configured something else in the Set up database step, select that and set the corresponding options)

- Server Domain should be

git.example.lan(or whatever you’re actually using),

Forgejo Base URL should behttp://git.example.lan - Ignore the Email Settings - Forgejo can be easily configured to use system sendmail (dma), but (at least in version 1.19) only in the app.ini, not in the web interface, so we’ll do that later.

- Check the Server and Third-Party Service Settings settings for settings that look relevant for you.

- I think it makes sense to create the administrator account right now (Administrator Account Settings), even more so if you disabled self-registration.

- Most settings can be easily changed in

/etc/forgejo/app.inilater, so don’t worry about them too much.

Once you’re done configuring, click Install Forgejo and a few seconds later you should be

on the dashboard (if you created an administrator account) or at the login/register screen, where you

can create an account to then get to the dashboard.

So far, so good14, but we’re not quite done yet - some manual configuration in the app.ini is needed!

Further configuration in Forgejos app.ini

Stop the forgejo service:

# systemctl stop forgejo.service

While at it, you could make /etc/forgejo/ read-only for the git user (Forgejo shouldn’t add any

files after the initial configuration):

# chmod 750 /etc/forgejo

For the same reason you could make the app.ini read-only, like:

# chmod 640 /etc/forgejo/app.ini

But note that Forgejo might still modify the app.ini later, especially when running a new version

for the first time, which might add new options!

Now (as root) edit /etc/forgejo/app.ini

NOTE: You’ll probably find the Configuration Cheat Sheet and the Example app.ini that contains all options incl. descriptions helpful.

I recommend the following changes (in the order of where I put them in the app.ini):

- Forgejo allows uploading files to git repos through the web interface.

By default the file size for uploads

is limited to 3MB per file, and 5 files at once. To increase it, under the

[repository]section, add a[repository.upload]section with a line likeFILE_MAX_SIZE = 4095(that would be 4095MB, about 4GB) andMAX FILES = 20It’ll look somehow like this:Similar restrictions exist for attachments to issues/pull requests, configured in the... [repository] ROOT = /var/lib/forgejo/data/forgejo-repositories [repository.upload] ;; max size for files to the repo via web interface, in MB, ;; defaults to 3 (this sets a limit of about 4GB) FILE_MAX_SIZE = 4095 ;; by default 5 files can be uploaded at once, increase to 20 MAX_FILES = 20 [server] ...[attachment]sectionsMAX_SIZE(default 4MB) andMAX_FILES(default 5) settings. - In the

[server]section add a lineHTTP_ADDR = 127.0.0.1to ensure that Forgejo only listens on localhost and is not reachable from the outside at all, except through nginx. - By default LFS data uploads expire after 20 minutes - this can be too short for big files,

slow connections or slow LFS storage (git-lfs seems to automatically restart the upload then -

which means that it can take forever and use lots of traffic)..

If you’re going to use LFS with big uploads, increase this limit, by adding a lineLFS_HTTP_AUTH_EXPIRY = 180m(for 180 minutes) to the[server]section. - Similarly there are timeouts for all kinds of git operations, that can be too short.

I ran into the problem that a migration of a big repository from our old Gitlab server timed out and left the repository in an inconsistent state (due to a bug in Forgejo/Gitea that should be fixed in the next version I wasn’t even warned about this in the web interface, there were only some log messages).

Anyway, I increased all those git timeouts by adding a[git.timeout]section below the[server]section:I increased all timeouts to factor 10 (by adding a 0 at the end); probably not all these timeouts need to be increased (and if, then maybe not this much)… use your own judgement, this worked for me ;-);; Git Operation timeout in seconds ;; increase the timeouts, so importing big repos (and presumably ;; pushing large files?) hopefully won't fail anymore [git.timeout] DEFAULT = 3600 ; Git operations default timeout seconds MIGRATE = 6000 ; Migrate external repositories timeout seconds MIRROR = 3000 ; Mirror external repositories timeout seconds CLONE = 3000 ; Git clone from internal repositories timeout seconds PULL = 3000 ; Git pull from internal repositories timeout seconds GC = 600 ; Git repository GC timeout seconds - As Forgejo is the only service running under the

gituser, it makes sense if it uses/home/git/.gitconfiginstead of its default of/var/lib/forgejo/data/home/.gitconfig, which also is currently buggy. This also allows to usegit config --global foo.bar 123asgituser to modify git settings on the server.

Add the following section to app.ini:and copy the .gitconfig that has already been written to the other directory to;; use the .gitconfig in the git users homedir, makes customization easier ;; also works around https://codeberg.org/forgejo/forgejo/issues/869 [git] HOME_PATH = /home/git/home/git/and make sure that it belongs to thegituser and group:

# cp /var/lib/forgejo/data/home/.gitconfig /home/git/

# chown git:git /home/git/.gitconfig - By default LFS files are stored in the filesystem, in

/var/lib/forgejo/data/lfs. In the[lfs]section you can change thePATH = ...line to store elsewhere, but you can also configure Forgejo to store the files in an S3-like Object-Storage. More information on that in the object storage subchapter below. - Enable sending E-Mails with sendmail/dma by changing the

[mailer]section like this:[mailer] ;; send mail with systemwide "sendmail" (actually dma in our case) ENABLED = true PROTOCOL = sendmail FROM = "Forgejo Git" <noreply@yourdomain.com>

When you’re done editing the app.ini, save it and start the forgejo service again:

# systemctl start forgejo.service

You can test sending a mail by clicking the user button on the upper right of the Forgejo page

(“Profile and Settings”), then Site Administration, then Configuration and under

Mailer Configuration type in your mail address and click Send Testing Email.

Enforce that git user can only use SSH through Wireguard

While the Forgejo web-frontend can only be reached through Wireguard, accessing the Git repositories with SSH is still allowed from any IP (but of course secured through SSH public key authentication).

If you fear that one of your users might accidentally expose their SSH private key (for example by

uploading the configuration part of their $HOME directory to Github15),

as an additional safety-measure you could disallow the git user to login through SSH from any IP

that’s not in your Wireguard VPN. Other users can still log in from any IP, so make sure that you

and other people with administrative access to the server don’t publish your private key :-p

NOTE: If your server supports taking a snapshot, doing this now might be a good idea, in case something goes wrong with the SSH configuration and you can’t log in anymore.

This is done by editing /etc/ssh/sshd_config (as root), and adding the following lines at

the end of the file:

# only allow git user to login from wireguard VPN network (172.30.0.X)

# by denying access from all IPs ("*") except for those ("!172.30.0.0/24")

Match Address !172.30.0.0/24,*

DenyUsers git

If you’re using a different network than 172.30.0.X for Wireguard, change the Match Address line accordingly.

Now tell the sshd service to reload its configuration:

# systemctl reload sshd

and make sure that it went well:

# systemctl status sshd

(check the output for errors complaining about invalid configuration)

General hints for using Forgejo

If you’ve used Github or Gitlab before, the user interface should be familiar; if you’re not sure how something is done, consult the Forgejo user guide and/or Forgejo administrator guide. If that doesn’t answer your questions check the Gitea documentation or ask the Forgejo community.

Remember that to use Git you’ll need to add your SSH public key to Forgejo (User Button on upper right ->

Settings -> SSH / GPG Keys -> [Add Key], paste the contents of $HOME/.git/id_rsa.pub)

Sometimes you may want/need to use the Forgejo command line interface. Keep in mind that:

- You need to run it as

gituser, for example with$ sudo -u git forgejo command --argument - You need to specify the Forgejo work path, either with the

--work-path /var/lib/forgejo(or-w /var/lib/forgejo) commandline option or by setting theFORGEJO_WORK_DIRenvironment variable ($ export FORGEJO_WORK_DIR=/var/lib/forgejo) before callingforgejo - You need to specify the path to the config (app.ini) with

--config /etc/forgejo/app.ini(or-c /etc/forgejo/app.ini).

So all in all your command might look like:

$ sudo -u git forgejo -w /var/lib/forgejo -c /etc/forgejo/app.ini admin user list

For convenience, you could create a

/usr/local/bin/forgejo.shwith the following contents:#!/bin/sh sudo -u git forgejo -w /var/lib/forgejo -c /etc/forgejo/app.ini "$@"and make it executable:

# chmod 755 /usr/local/bin/forgejo.shNow if you want to call

forgejoon the commandline (for the default system-wide installation in/var/lib/forgejo), just use e.g.$ forgejo.sh admin user listinstead of the long line shown above.

You can always call forgejo and its subcommands with -h or --help to make it output usage

information like available options and (sub)commands, for example

$ forgejo admin user -h

to show available subcommands to administrate users on the commandline.

Local storage vs. object storage for LFS

Instead of storing the LFS files locally on the server (by default under /var/lib/forgejo/data/lfs/),

Forgejo (and Gitea) supports storing them in an (Amazon S3-compatible)

object storage. If your server is at risk of running out of diskspace, it might be easier/cheaper

to host the LFS files in an object storage instead of renting a bigger server.

While Amazon S3 itself is way too expensive, there are open source solutions (like MinIO or Ceph) that implement S3’s protocol, and providers that use those to offer S3-like object storage for much more affordable prices, starting at around $10/month for 1TB16.

To use such an object storage, the [lfs] section in /etc/forgejo/app.ini would look kinda like this

(see also documentation):

[lfs]

; PATH = /var/lib/forgejo/data/lfs ; only used for local storage

;; adjust these settings for the logindata of your object storage provider

STORAGE_TYPE = minio

MINIO_ENDPOINT = endpoint-url.com

MINIO_ACCESS_KEY_ID = YOUR_ACCESS_KEY_ID

MINIO_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY = YOUR_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

MINIO_BUCKET = gitea

MINIO_USE_SSL = true ; encrypt connections to the object storage

;; if your object storage provider needs it, set the location

; MINIO_LOCATION: us-east-1

(Refer to your object storage providers documentation on how to get the needed keys and what the endpoint is.)

One thing to keep in mind with object storage is that when making backups of Forgejo, the data in object storage isn’t easily backed up together with the rest, because it’s not on the same server. So unless you trust the object storage provider to keep your data with enough redundancy that it will never get destroyed (if their datacenter burns down, for example), you need to back up the data in the object storage in an additional step after the “normal” backup of your server. Rclone is a great tool to access object storage (and lots of other kinds of remote storage) and allows you to mount the object storage as a local virtual filesystem, so you can copy its contents to a local backup disk, for example (or copy it to a different cloud storage; you could probably even run restic on the mounted folder).

Migrating to/from object-storage

You can also migrate to object-storage later (or back from object-storage to local storage). (You don’t need this when setting up forgejo initially, only if commits with LFS data have already been pushed to the server!)

To migrate, first stop Forgejo (# systemctl stop forgejo.service).

To migrate LFS from local storage to object-storage (while the app.ini still has local storage

configured!) run:

$ sudo -u git forgejo -w /var/lib/forgejo/ -c /etc/forgejo/app.ini migrate-storage -t lfs -s minio --minio-endpoint endpoint-url.com --minio-access-key-id YOUR_ACCESS_KEY_ID --minio-secret-access-key YOUR_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY --minio-bucket gitea --minio-use-ssl

To migrate from S3-like object-storage back to local (while the app.ini still has minio object

storage configured!) run:

$ sudo -u git forgejo -w /var/lib/forgejo/ -c /etc/forgejo/app.ini migrate-storage -t lfs -s local -p /var/lib/forgejo/data/lfs

After the migration is done, adjust /etc/forgejo/app.ini for the new storage type and start Forgejo

again (# systemctl start forgejo.service).

When you’re done migrating to object storage, you may want to delete /var/lib/forgejo/data/lfs/*

to free up the disk space.

Backups with restic

Restic is a powerful backup tool that’s easy to install and relatively easy

to use.

Restic creates incremental backups - each time it’s run for a specific path, it creates a new

snapshot for it (that can later be restored), but only saves the difference to the last snapshot,

which is pretty space-efficient and fast. Furthermore, it compresses the backups

(saves even more space) and encrypts them, so if someone gets access to wherever you store your

backups (for example backup space provided by your hoster), they still can’t access your data

(unless the attacker somehow managed to steal your password as well, but it’s not stored with the

backups, of course).

It directly supports storing the backups on a local path, or on another server with a variety of protocols including SFTP, the Amazon S3 protocol and a custom REST protocol - and when combining it with Rclone (which it supports out of the box, if Rclone is installed), it supports literally dozens of additional protocols and providers, including FTP(S), WebDAV (ownCloud/Nextcloud), Google Drive, MS OneDrive, SMB/CIFS (Windows share) and more.

NOTE: If you don’t want to do (automated) backups because setting up the server is easy enough and all local git clones contain the whole history anyway:

Yes, that’s mostly true, but please keep in mind that when using git LFS, the local clones by default do not have the whole history of files managed with LFS, but only the version currently checked out. However, calling$ git lfs fetch --alldoes download all git LFS objects (but of course uses a lot more disk space on your PC).

Installing restic

Download their latest release for your platform

(probably linux_amd64) and extract it:

$ bunzip2 restic_0.15.2_linux_amd64.bz2

(adjust filename for the version your downloaded)

Then copy it to /usr/local/bin/restic:

# cp restic_0.15.2_linux_amd64 /usr/local/bin/restic

and make it executable:

# chmod 755 /usr/local/bin/restic

Optional: Install and configure Rclone

If you want to upload your backups to a storage provider not directly supported by restic (check this list), you’ll need to install Rclone.

You can download it at https://rclone.org/downloads/ - I chose the .deb version for

“Intel/AMD - 64 Bit” (I guess it should work on most recent-ish versions of Debian, Ubuntu and derivates)

and installed it with:

# dpkg -i ./rclone-v1.62.2-linux-amd64.deb

NOTE: Ubuntu provides an rclone package in their repo as well, but it’s older (1.53). For best compatibility with storage providers, using the latest version is probably best.

(I couldn’t get 1.53 to work with Google Drive, I think the authorization link changed since 1.53 was released).

You can configure a remote (incl. login-data etc) with

# rclone config

(this doesn’t generally require root privileges, but as you’re going to use this with restic

that will be run as root, configure rclone as/for root as well)

Find your provider in this list and click the (Config) button

on the right to get detailed provider-specific instructions (make sure to read them completely,

for example for Google Drive, their

Making your own client_id section is said

to be important to get decent performance).

Remember the name you chose for the remote, you’ll have to pass it to restic as “repository”